By Melanie Groß

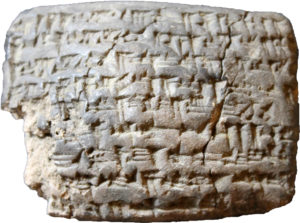

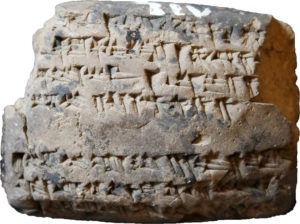

The Liagre Böhl Collection of the Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten (NINO) in Leiden comprises the largest collection of cuneiform clay tablets in the Netherlands. F.M.Th. de Liagre Böhl (1882–1976), Professor of Assyriology at Leiden University (1927–1952), had acquired more than 3,000 cuneiform tablets during his travels to the Middle East and at the European antiquity market. Shortly before the end of his professorship he sold the tablets to the NINO which still owns the tablets and keeps them safe in the so-called vault behind a thick metal door. In the Böhl collection one finds cuneiform sources from various different periods, including the Ur III, Old Assyrian and the Old Babylonian periods, and of various different text genres, including literary texts, school tablets, administrative documents and letters. About 700 tablets alone are Neo- and Late Babylonian legal and administrative texts.

Many of the cuneiform treasures of the Böhl collection are still unpublished – something which holds particularly true for the Neo-Babylonian collection. While the tablets have been filed by Böhl himself and partly studied by Govert van Driel (1937–2002), lecturer in Mesopotamian History and Archaeology in Leiden, the Neo-Babylonian collection is still largely unexplored. Only very recently, namely in the years 2018 and 2019, did Jeanette Fincke on behalf of the NINO establish a digital catalogue which systematically records every tablet of the collection, along with details and photographs. This catalogue will eventually be published online. In the second half of the year 2019 Lidewij van de Peut catalogued the entire Neo-Babylonian section. Thanks to Lidewij’s work it became clear that a great number of these records belong to one of two groups: administrative records from Uruk (primarily from the Eanna temple) and legal records from Sippar.

The cuneiform tablets of the Böhl collection share the fate of thousands of cuneiform tablets housed by numerous collections worldwide. As they came to light in the course of illicit excavations and were sold on the antiquity markets, we usually lack any archaeological information. It is but thanks to the systematic recording of the place of writing as well as the date of writing in legal cuneiform texts that we can classify and label the Neo-Babylonian Sippar tablets from the Böhl collection. While they were usually written in Sippar, they mostly date to the reign of the Achaemenid king Darius I, but there are also older documents (reaching back to the Neo-Babylonian period) and younger documents (dating to the early years of Darius’ successor Xerxes). The legal activities recorded in the texts concern payment obligations in silver and dates as well as investments of silver in business enterprises. Furthermore, they provide evidence for the lease of houses and the purchase of slaves and donkeys.

If we look into the people involved (the active parties to the transaction, the witnesses and the scribe), it becomes even more intriguing since the same people occur over and over in these texts. Entire families which are, in fact, already known to scholars, come alive. Remnants of their archives had been identified in the Lewis Collection of the Free Library of Philadelphia and the Babylonian Collection of the Yale University. These collections house a significant number of documents belonging to members of the Balīhû family, the Maštuk family and the Ṣāhit-ginê family (or branches thereof) who lived in Sippar. Being engaged in trading businesses, they were active as creditors, investors, buyers and lessors – in short, as entrepreneurs. The traces of their activities had surfaced in the Böhl collection already years ago, but the true extent only became obvious with the efforts undertaken by Lidewij.

While my research on these families and their business archives began a few years ago by studying the tablets in the US, it is high time to look into the material in Leiden. It is currently pure adventure to dive into the (in times of Covid-19, the photographs of the) Sippar tablets in the Böhl collection and the stories they tell. A single document about, for instance, a loan of silver of Bēl-iddin from the Maštuk family might not be extremely telling in the first place, but to have in total about 60 tablets at hand documenting decades of business activities and family affairs of Bēl-iddin and his relatives, makes it possible to reconstruct the life of Sipparean traders during a period when the Achaemenid kings exercised control over the Babylonian territory.