By Ivo Dos Santos Martins

Until 6 May 2018 the National Museum of Antiquities (Rijksmuseum van Oudheden) in Leiden is hosting the exhibition Fascination with Persepolis. This exhibition is inspired by the work of photo-historian Dr. Corien Vuurman whose doctoral dissertation was published in 2015. Although relatively small, the exhibition takes full advantage of its limited space to convene a coherent and compelling narrative of the men and women who contributed to unveiling Persepolis anew. Not included in this iconographic exhibition for obvious reasons (there isn’t a single image that depicts him), is the Portuguese priest Fryer António de Gouveia (1575-1628), who was one of those rediscoverers.

A walk through the exhibition

Such a long fascination is fittingly represented by two diametrically opposed exhibits. At the entrance of the ‘Muse hall’, the visitor is greeted by a 17th century fanciful engraving while, at the far end of the gallery, a 21st century 3D reconstruction plays on a small monitor. The engraving is the artwork of Jan Janzoon Struys, who visited Persepolis around 1672, and was one of the first depictions of the site to have reached Europe. The lack of realism is striking.

The digital reconstruction was released in 2004 as part of the documentary Iran: Seven Faces of Civilization by Iranian scholar Dr. Farzin Rezaeian. In it, the entire complex is recreated from drone footage in accordance with paper-based reconstructions by Frederich Krefter (1971).

Between the dreamlike imagination of the oldest drawing and the digital accuracy of modern reconstructions, a diverse range of images and objects illustrates the journey to rediscovery of ancient Persepolis. Plates, photographs, modern objects and archeological artifacts illustrate the work of travelers, archaeologists, diplomats and photographers.

Several books from the Leiden University Library collection are among them. Noteworthy are the travel accounts by Struys (1676), Cornelius de Bruijn (1711) and Jean Chardin (1711), the Atlas of P. Coste and E. Flandin (1851) and the panoramic photographs of Marcel Dieulafoy (1894-5) and E. F. Schmidt (1953). An album showing two platine-printed photographs taken by Albert Hotz, who is credited as the first Dutch photographer to have visited the Persepolis Plain in 1871, is part of the same collection.

Of the diverse iconographic material reunited in the exhibition, the pioneering photographs of the Italian Luigi Pesce (1858), the semi-professional photographs of the Iranian Sam Ala of the Khan Estakri family (1930’s), that of German writer Annemarie von Nathuis (1924), several Iranian family photos of the 1950-60’s (coll. Kanran Najafzdeh), and the professional photographs of Harold Weston (1921) and a photograph of Queen Julianna and Shah Reza Pahlavi amid the columns of Persepolis (1963) stand out.

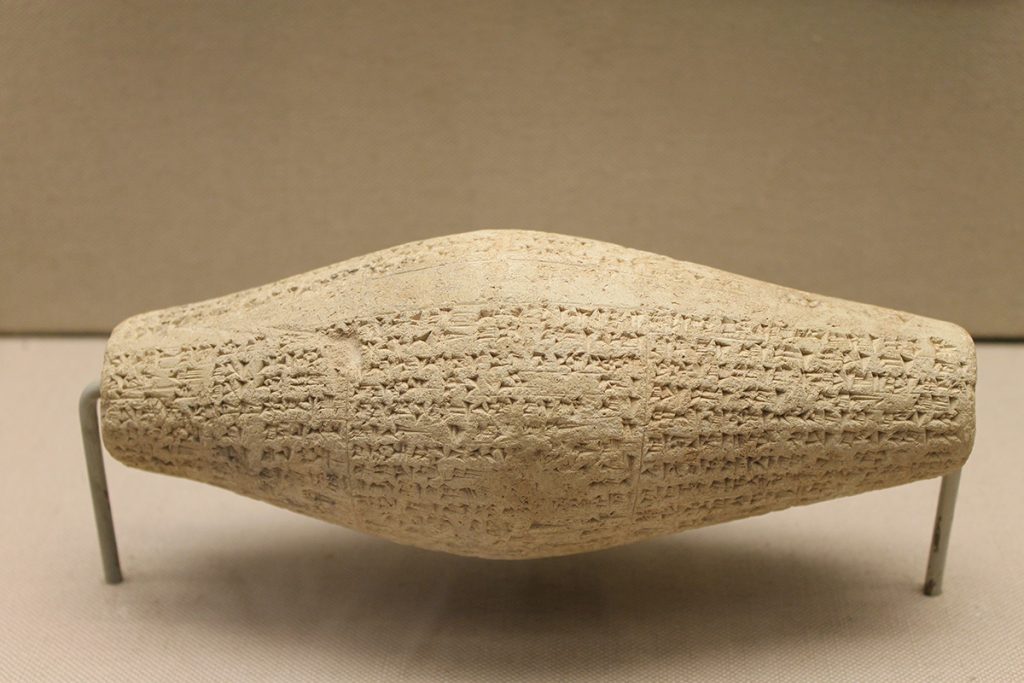

The object on display which no doubt lures the attention of any visitor is a complete nineteen century photographic set including a concertina-type travel camera, plates and developing chemicals and accessories from 1858 (Ruud Hoff collection). A small vitrine contains a few archaeological artifacts found at Persepolis. These include two bags with fifty-five pottery sherds from the 1923 Ernest Herzfeld’s excavations (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin coll.); three clay tablets from Persepolis archives recording legal matters (RMO coll.); and a small stone-slab from the palace of Darius I depicting a Persian soldier in bas-relief (RMO coll.). Regrettably, little reference is made to the major archeological excavations initiated in 1931. These excavations, which brought to light most of the complex, were conducted under the direction of Ernest Herzfeld (1931-1934) and Erich Schmidt (1934-1939) and promoted by the Oriental Institute of Chicago.

Older “fascinations”

Fascination with Persepolis centers on Europeans travelers and their iconographic records of the last four centuries. However, the appeal of the ruins of Čehel Menār captured the imaginations of earlier European travelers as well. Moreover, European curiosity for Persepolis extends far beyond iconographic sources and archeological excavations. As is briefly mentioned in the exhibition, European visitors have traversed the Marv Dasht plain since the 14th century. The Italians Fryer Odoric of Pordenone (ca. 1318) and Josafat Barbaro (1474) were the first to leave a written records of their visits (Vuurman 2015:26).

Gradually, European voyages through Safavid Persia (1502-1736) become more numerous and frequent. Indeed, António de Gouveia reports that, by the early 17th century, the great affluence of visitors was felt as a nuisance to the inhabitants of the Marv Dasht plain: “The inhabitants of the place, oppressed, or bored of the many people who came to see this marvel, armed themselves several days against it working as much on unmaking it, as what it probably took to make it…” (Gouveia, 1611: f.32).

This was a result both of the European age of expansion and of the strategic importance of Safavid Persia as a counterweight to the growing power of the Ottoman Empire. The voyages of Geofry Ducket (1569), Pietro della Valle (1621), Garcia de Silva e Figueroa (1619), Jean Chardain (1666), J.J. Struys (1672) and Cornelius de Bruijn (1704-5) are to be understood within this context.

Besides these, several Portuguese voyagers journeyed in Persia during this period. With the capture of the island of Hormuz (Jazīreh-ye Hormoz) in 1515, a privileged gateway into Persia was opened and various Portuguese ventured inland: diplomats seeking the Sha’s alliance, missionaries linking up with isolated Christian communities, shipwrecked seafarers wishing to reach Europe via Aleppo.

António de Gouveia

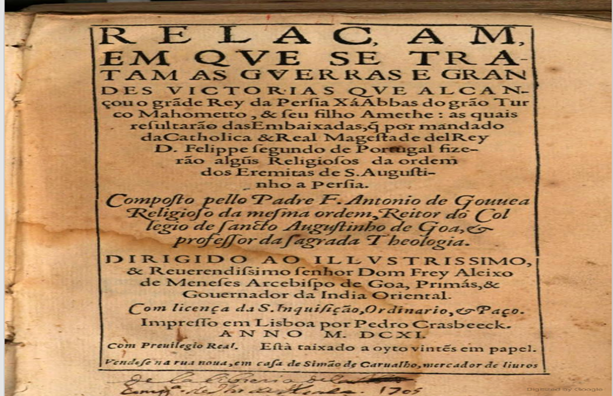

The account of António de Gouveia (or Gouvea following its original spelling), an Augustinian missionary and diplomat, stands out from other Portuguese travel literature. His book, Relaçam em que se tratam as guerras e grandes victorias que alcançou o grãde Rey da Persia Xá Abbas do grão Turco Mahometto, & seu filho Amethe (…),was published in 1611. In it, Gouveia significantly contributes towards the identification of Persepolis and the first modern report on the cuneiform writing system.

António de Gouveia was born in 1575 in Beja, Portugal. Professing as an Augustinian in Lisbon, he was posted to Goa in 1596. A few years later, Gouveia was chosen to lead the ninth Portuguese embassy to Persia. On 15 February 1602 Gouveia’s party set sail from Goa only arriving at Hormuz on April 10th. Another month would pass before the Portuguese delegation was allowed to set foot on Persian shores and start its search for the court of Shah ‘Abbās I (1588-1629), which they would find in late September in the city of Maxed (Mashhad) (Carreira 1980:93).

On the way there, António de Gouveia collects a vast array of information not only on Safavid Persia of political, religious and ethnographical interest, but also on historical matters. By virtue of his religious education, he shows considerable knowledge not only of Biblical but of Classical texts as well. Such background proves useful when Gouveia seeks to make sense of the oral information he receives and the reality of what he sees.

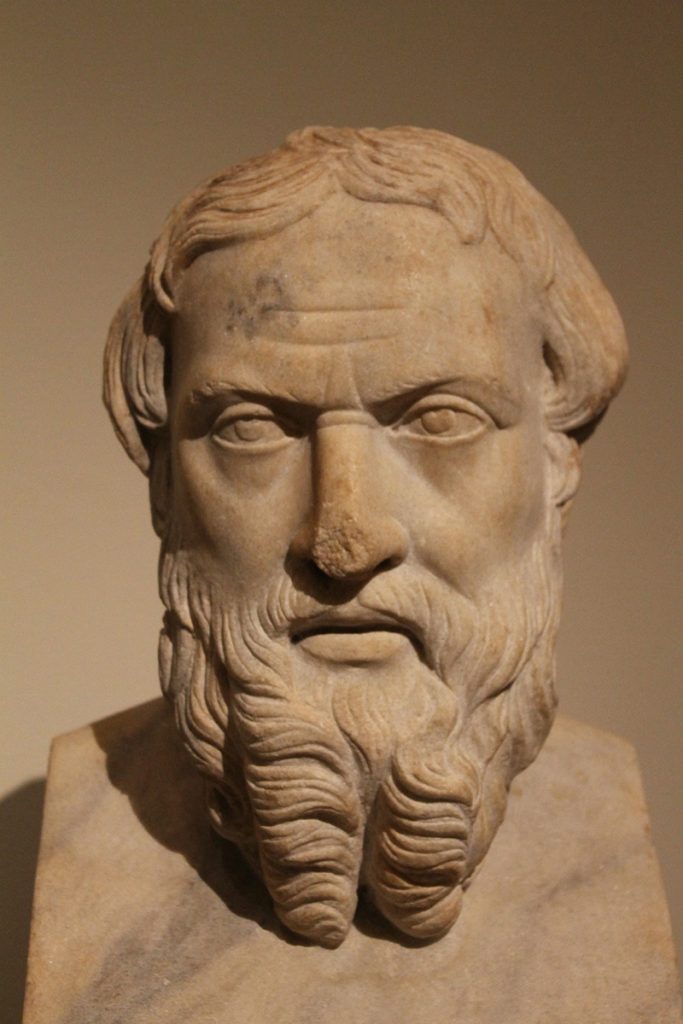

After a stay in Lara, the embassy reached the city of Xiraz (Xirás) on 15 June. Gouveia identified this city with Persepolis saying that in ancient times it was “the head of all the Kingdom of Persia” (Gouveia 1611, f.25v.). Gouveia associates to this city the story of Persepolis’ destruction by Alexander at the request of a friend. He was perhaps quoting from memory since he names Campaspe of Larissa instead of the Athenian Thais (Diodorus Siculus, Universal History VII:71).

“(Xiraz) is today thriving, even though it has been destroyed one time by the Tartars and another by the Arabs, not to speak of that ancient ruin to which Alexander the Great has once reduced it, ordering its burning to please Campaste (sic) his friend, who had so asked him, though later he repaid that damage in ordering its reconstruction.” (Gouveia 1611 [1609], f.26)

Evidently, Xiraz was not Persepolis. But when Gouveia reached nearby Chelminirá (Čehel Menār, i.e. “forty minarets”) he partially corrected the mistake. Refuting Joseph Barbaro’s claim that Xiraz had once stretched to the ruins, Gouveia reckons that these were potentially the remnants of an older city, eventually ancient Xiraz (Gouveia, 1611, f.31).

In a lengthy description of the ruins Gouveia mentions several details like the column’s capitals with “beautiful figures”, the dimensions of the columns and the big stone gates with “lions and other ferocious animals, who still appeared to want to instill fear” (Gouveia, 1611, f.31v.).

Gouveia’s interpretations of the tombs are drawn from Biblical texts and, unlike Barbaro before him (Vuurman 2015: 26), he is somewhat able to make an accurate identification… by chance. He attributes the three tombs to Cyrus, the Biblical Queen Vashti and the King Ahasuerus, whom he dubs to be one of the Artaxerxes (Gouveia, 1611 f.30). And indeed, one of Persepolis’ tombs belongs to Artaxerxes III (Carreira 1980:93).

All in all, António de Gouveia tends to be cautious when putting forward his interpretations. For example, he precludes himself from speculating on who might have been the builder of the complex, preferring instead to refer to a source which he cannot read:

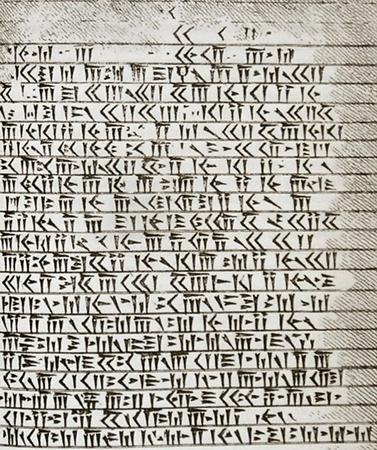

“The letters which declare the foundation of this complex structure, and which should declare its author as well, though they are at several places quite distinct; alas there is no one who can read them, because they are neither Persian, nor Arabic, nor Armenian, nor Hebraic which are (the scripts) which today roam through those parts, and therefore everything contributes to let forget what the ambitious King desired so much to make eternal.” (Gouveia, 1611: f.32)

Thankfully, these characters and the location of Persepolis didn’t remain enigmatic for much longer. Some ten years later, Gouveia’s diplomatic successor, the Spanish Garcia de Silva e Figueiroa, links Čehel Menār with Persepolis. In 1704-5 Cornelius de Bruijn’s reproduction of those same characters initiates 150 years of efforts to decipher cuneiform.

References

Achour-Vuurman, Corien J.M. (2015), Fascinatie voor Persepolis: Europese perceptie van Achaemenidische monumenten in schrift en beeld, van de veertiende tot het begin van de twintigste eeuw. Gronsveld: Barjesteh van Waalwijk van Doorn & Co’s Uitgeversmaatschappij.

Gouveia, António de (1611), Relaçam em que se tratam as guerras e grandes victorias que alcançou o grãde Rey da Persia Xá Abbas do grão Turco Mahometto, & seu filho Amethe (…). Lisboa: Pedro Crasbeeck, 25-32.

Carreira, José Nunes (1980), António de Gouveia e a Escrita Cuneiforme, in: Do Preste João às ruínas da Babilónia : viajantes Portugueses na rota das civilizações orientais. Lisboa: Editorial Comunicação, 83-94.