By Uzume Wijnsma

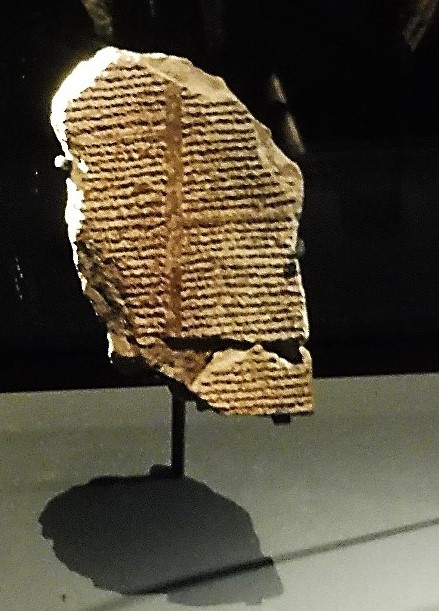

It’s 6.30 AM. And instead of ignoring my alarm clock in bed, which I normally do at this hour, I’m standing outside looking at a barely visible piece of rock. It is located half-way up a mountain. And an ugly scaffold obscures most of it from view for the passers-by down below. Nevertheless, there I am – in the cold, camera in hand – waiting for the moment that the first rays of sunlight will illuminate it slightly. Now, I know that the light won’t help me to discern the cuneiform inscriptions that cover it – they are badly weathered – but it just might help me to see the figurative relief in better detail. If it does, then missing both my precious sleep and my breakfast will have been completely worth it. I am standing, after all, below one of my favorite rock reliefs from the entire ancient Near East: the monumental Bisitun inscription.

The Bisitun inscription was created by one of the first kings of the Achaemenid Empire – Darius I – to commemorate his seizure of the throne in 522 BC. It tells us about the court intrigues which preceded Darius’s rise to power, the empire-wide rebellions that broke out upon his coronation, and his brutal defeat of all of those rebellious “liar-kings” (which ranged from simply killing them, to mutilating their bodies and impaling them near capital cities). This alone renders the inscription extremely valuable to the study of the Achaemenid Empire. Additionally, because the inscription was written in three languages – Elamite, Old Persian and Babylonian – it was of essential importance to the decipherment of cuneiform in the nineteenth century. One often hears that it was the “Rosetta Stone” of the field of Assyriology. So, as a PhD student in the field of Achaemenid Empire studies, I was dying to see the inscription with my own eyes.

The Bisitun inscription was just one of the many marvels that I saw on our trip to Iran, however – a trip from which we have only just returned (dates: 19 April – 6 May). We started in Tehran, quickly drove to the snowcapped mountains of Ecbatana (Hamadan), on to the chilly environs of Bisitun (Kermanshah), and from there to the sunny, over 30 degrees Celsius sites of Susa and Chogha Zanbil (Shushtar). From Shushtar we went to Shiraz, where we finally got to see Persepolis and Naqsh-e Rustam; and from there we drove (via Pasargadae) to the beautiful city of Isfahan to relish in some modern-day Persian culture. While most of us went home at that point, some of us went on to Kashan to give an Assyriology workshop to a lovely group of Iranian archaeology students. In all, we covered more than 2420 km in ca. seventeen days. So I can assure you that by the end of the trip our bus had become our second home. There’s nothing like a handful of 10-hour-days on the highways to make you bond with a vehicle.

“We” and “us” in that paragraph, by the way, refers to a small group of (mostly) Assyriologists. For all of us, it was the first time that we went to Iran; and for most of us, it was the first time that we saw cuneiform inscriptions “in the wild,” rather than in some European museum. That was quite something. I mean, you can read about a monument, you can look up the pictures in a dusty book or a scholarly article, but there’s nothing like actually standing in the cold and peering at a frustratingly invisible relief to make you understand an inscription and the place it occupies in the surrounding landscape. Being there, standing there, walking around and taking everything in, gives you a level of historical understanding that reading a published text on your couch back home just cannot. That is not to say that the latter is inferior to the former (as a historian who loves to read texts on her couch, I’d be the last one to claim that). Rather, both are elements of one inseparable whole.

Unfortunately, it is well known that Assyriologists have less easy access to the “being there”-aspect of their discipline than many other scholars of antiquity. Assyriologists can visit cuneiform inscriptions in Iran, of course; or in Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon etc. But Iraq – the cradle of the discipline – continues to be a country that few universities feel safe to send their students to. Who knows when that will change. One thing I do know is that I will not wait for that change. If I cannot go to (southern) Iraq, or to (parts of) Syria, then I’ll just visit all of the other countries. And Iran remains on the top of that list. It is a country with so many splendid monuments, mountains, deserts and cities that one trip does not even begin to exhaust what it has on offer. So, I will go back there. And to be completely honest, I’m already planning my next trip…