The Egibi/Nūr-Sîn archive is the biggest private archive to have survived from the Neo-Babylonian and Achaemenid period. Dating to ca. 606–484 BCE, the archive contains about 1,700 tablets, but when one includes fragments and duplicates of tablets, the number can rise close to 2,000. According to first counts, however, the estimated total number of tablets had been about three to four thousand. The archive was found by the locals in the ruins of ancient Babylon in the 1870s–1880s, and then sold to various museums around the world. A small portion of the tablets was reportedly found in a pot, which possibly had been used as a fumigation vessel and only secondarily as a vessel for tablet storage.

Figure 1: Inscribed pots from Babylon. Some legal tablets from the Egibi archive are said to have been found in one of these pots (BM 92421). Both the tablets and the pot was sold to the British Museum. © Trustees of the British Museum

The biggest bunch of tablets was bought by the British Museum, with their representative George Smith intermediating the process in Iraq (cf. cf. Panayatov and Wunsch 2014). Due to its size the archive has been difficult to study. More than 600 tablets have been published by Cornelia Wunsch (1993, 2000). Another 144 tablets have been published by Kathleen Abraham (2004). Besides these main publications, a handful of tablets have been published in various articles by other researchers. One can also read about the content of the documents in the Egibi archive, both published and unpublished, via the NaBBuCo website.

Figure 2: George Smith (Source: Wikipedia)

Figure 2: George Smith (Source: Wikipedia)

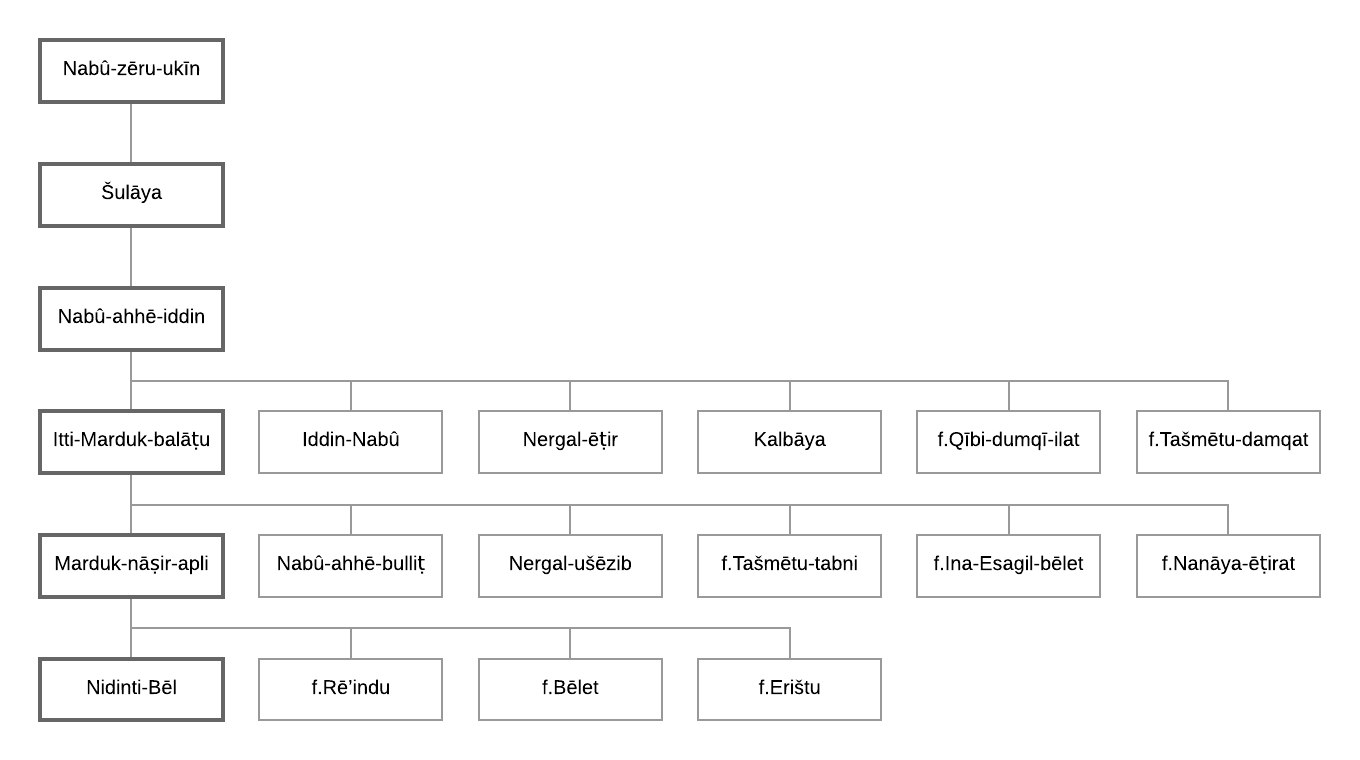

The Nūr-Sîn archive was partially merged with the Egibi archive when Nuptāya, daughter of Iddin-Marduk, descendant of Nūr-Sîn married Itti-Marduk-balāṭu, son of Nabû-ahhē-iddin, descendant of Egibi. The archive of the Egibis covers the activities of five generations, and mentions the sixth by name (Nabû-zēru-ukīn).

Figure 3: The six generations of the Egibi family (the reconstruction follows Wunsch 1995/1996: 34). The individuals on the left side are the (“eldest”) sons that were in charge of the family business, the individuals preceded by ‘f.’ are women. Created with Lucidchart.

The archive contains documents about family matters, such as marriage and inheritance related documents, but the majority of the tablets is related to the entrepreneurial activities. The Egibis owned urban real estate, fields, gardens, boats and hundreds of slaves. Many of these slaves acted as agents for the family, helping them run their business with a mixture of dependency and freedom. The Egibis established business partnerships (Akk. harrānu), which were concerned with trade in commodities, such as barley, dates and onions, but also wool. Several members of the Egibi family collected taxes and tolls for the state. The taxes were collected from individuals, families or other units, based on the tax type. Marduk-nāṣir-apli, for example, was collecting indirect taxes, such as payments for bridges (Akk. gimru/gišru), but also direct taxes, such as payments replacing service (Akk. ilku), payments for military equipment (Akk. rikis qabli), payments from bow units (Akk. pānāt qašti), and collection of flour (Akk. qēmu).

Figure 4: New York Times article headline (Source: New York Times)

Figure 4: New York Times article headline (Source: New York Times)

In 1979, November 30, The New York times wrote an article titled ‘Egibi & Co., The Oldest Bankers’. However, the Egibis were not bankers, but entrepreneurs. It is true that the majority of the documents in their archive are promissory notes, but these were related to their business activities, and not deposit banking (cf. Wunsch 2002: 247). Such promissory notes could relate to various activities. For example, they could be drawn up when purchase fees were divided into parts and paid over a period of time. They could also be drafted in the context of trade or land lease and simply record an obligation to deliver commodities (e.g. barley, dates, onions). Besides that, they could also be connected to payment of taxes (e.g. ilku) – the Egibis paid the tax in silver, and the landowners had to pay the Egibis a share of their harvest. When the harvest failed, farmers ran into debts, and sometimes had to pledge their land or slaves. In case they could not repay after all, they had to sell their property in order to do so.

Due to the wide range of their business activities, the Egibis had high mobility in Babylonia and beyond. The Egibis were mainly active in the cities of Babylon and Borsippa, and the surrounding villages, but they also travelled to other locations, most notably the village of Šahrīn. Nabû-ahhē-iddin appears in the documentation from Opis (ca. 76 km from Babylon), and both his son, Itti-Marduk-balāṭu, and his grandson, Marduk-nāṣir-apli, travelled to Susa in Elam in order to secure and enlarge their business – activities which needed royal favour (cf. Wunsch 2007).

Figure 5: The maximal reach of the Neo-Babylonian Empire (626–539) (Source: Wikipedia)

Figure 5: The maximal reach of the Neo-Babylonian Empire (626–539) (Source: Wikipedia)

Besides covering a large geographical area with their activities, the Egibis were also socially well connected. They had contacts in the highest levels of the Neo-Babylonian empire. One of their family members, Nabû-ahhē-iddin was a court scribe. During the reign of Nabonidus he was even appointed as royal judge. The Egibis managed to keep their connections with the royal palace even during the Achaemenid period, as can be proven by Marduk-nāṣir-apli’s toll collecting activities (see above). However, during the lifetime of Marduk-nāṣir-apli’s son Nidinti-Bēl, the Egibis might have faced some difficulties. The archive was sorted out and deposited by Nidinti-Bēl during the first years of Xerxes I (486–465 BCE). The ‘end date’ of their archive, around 484 BCE, suggests that they might have been supporting the Babylonian revolts against Xerxes I.

Bibliography

- Abraham, K. 2003: “Property and Ownership in the Egibi Archive from Babylon”, Eretz-Israel: Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Studies 27, 1–9.

- Abraham, K. 2004: Business and Politics under the Persian Empire: The Financial Dealings of Marduk-nāṣir-apli of the House of Egibi (521–487 B.C.E.), Bethesda.

- Abraham, K. 2011: “An Egibi Tablet in Jerusalem”, Israel Exploration Journal 61, 68–73.

- Evers, S.M. 1993: “George Smith and the Egibi Tablets”, Iraq 55, 107-117.

- Kozuh, M. 2007: “The Egibis in English”, BiOr 64, 307–320.

- Panayotov, S.V. and C. Wunsch 2014: “New Light on George Smith’s Purchase of the Egibi Archive in 1876 from the Nachlass Mathewson”, in M. J. Geller (ed.), Melammu: The Ancient World in an Age of Globalization, Berlin, 191–215.

- Waerzeggers, C. 2003/2004: “The Babylonian Revolts Against Xerxes and the ‘End of Archives’”, AfO 50, 150–

- Wunsch, C. 1993: Die Urkunden des Babylonischen Geschäftsmannes Iddin-Marduk: Zum Handel mit Naturalien im 6. Jahrhundert v. Chr., Groningen.

- Wunsch, C. 1999: Neubabylonische Urkunden: Die Geschäftsurkunden der Familie Egibi”, in J. Renger (ed.), Babylon: Focus mesopotamischer Geschichte, Wiege früher Gelehrsamkeit, Mythos in der Moderne, Saarbrücken, 343–364.

- Wunsch, C. 2000: Das Egibi Archiv: 1. Die Felder Und Gärten, Groningen.

- Wunsch, C. 2002: “Debt, Interest, Pledge and Forfeiture in the Neo-Babylonian and Early Achaemenid Period: The Evidence from Private Archives”, in M. Hudson and M. van de Mieroop (eds.), Debt and Economic Renewal in the Ancient Near East, Bethesda, 221–255.

- Wunsch, C. 2007: “The Egibi Family”, in G. Leick (ed.), The Babylonian World, Abingdon and New York, 236–247.

Author: Maarja Seire

Published on 4 April 2019