Nope. Unlike “cheese”, eqīdu (Akkadian for “cheese”) doesn’t make you smile for the camera… No matter! Photography and Assyriology have met in many other ways. For the last century-and-a-half, they have grown together, feeding and learning from each other. Funny enough, despite its hi-tech aura Photography is actually the elder brother in this symbiotic relationship. Both came to light in the mid-19th century and were developed by technological and scientific breakthroughs brought about by several Victorian-era polymaths.

A shared midwife

William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) was one such polymath. He published extensively in different areas of knowledge: from etymology to mathematics, from spectral analysis to folklore. Today he is mostly remembered by his work on Photography and his contributions to Assyriology. In Assyriology, among several other contributions in translations and lexicography, Talbot is credited as a pioneer of the decipherment of cuneiform. In 1857, together with Henry Rawlinson, Jules Oppert, and Eduard Hincks he answered to challenge made by the British Royal Asiatic Society. Although his translation of the prism of Tiglath-Pileser I (BM 91033) was deemed “less positive and precise” (Rawlinson et al. 1857: 6), it was similar enough to prove that the cuneiform script had been decoded.

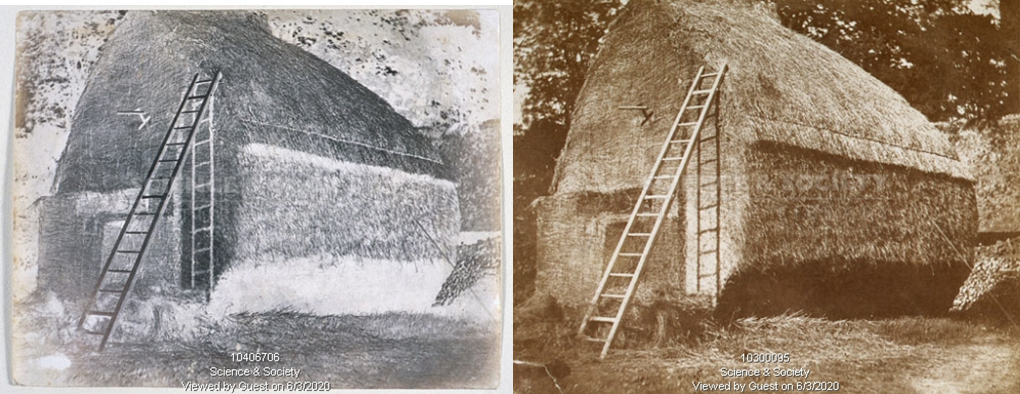

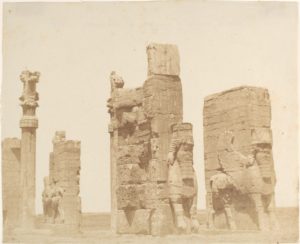

Already in 1841, Talbot had invented a new process of photography known as talbotype or calotype (Fig. 1). Talbot’s new photographic process was revolutionary. Using calotype paper (i.e. paper chemically prepared with silver nitrate and potassium iodide), Talbot was able to produce a negative image which had a relatively low exposition time and that, unlike the daguerreotype (a concurrent process invented in 1839), could be developed into several positive copies. It made photography less expensive and more portable (Fig. 2).

First encounters

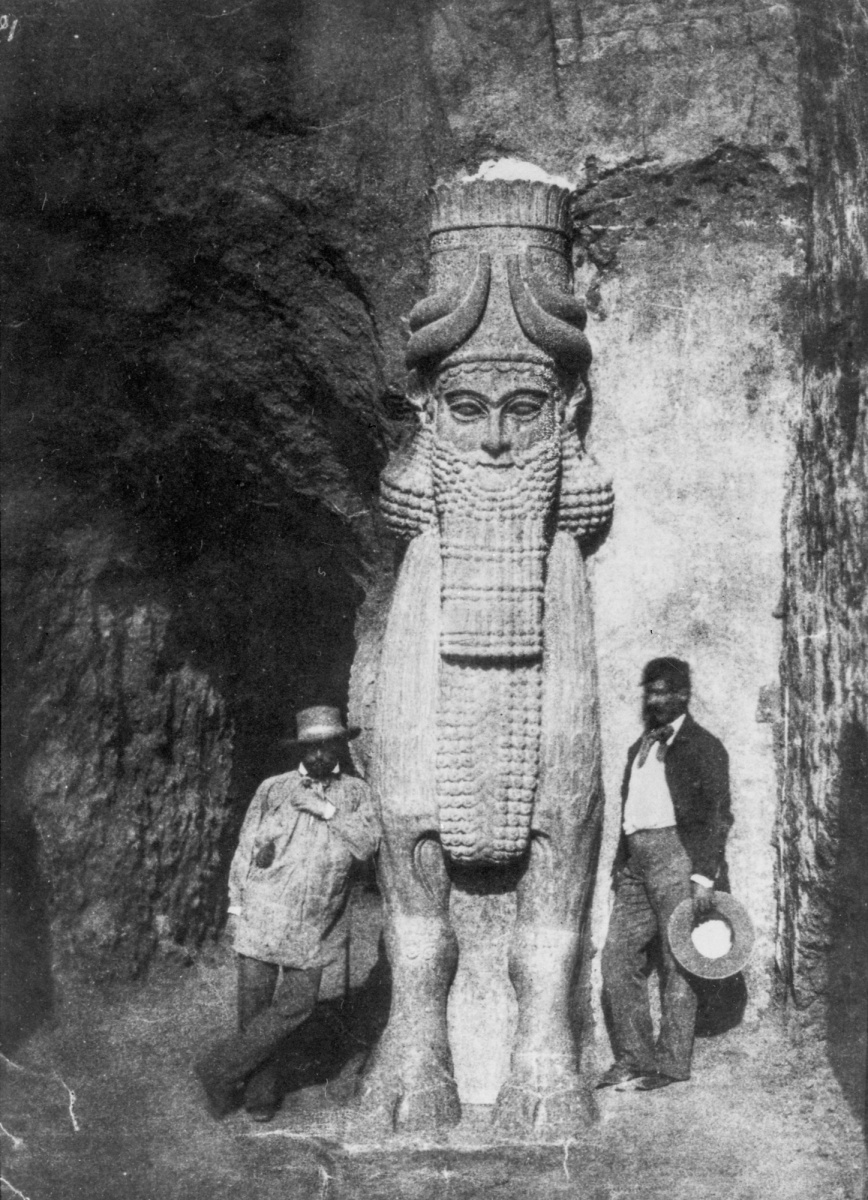

For Assyriology, it meant that the early excavators were able to use talbotype-photography to document their excavations. It is said, for example, that Gabriel Tranchand used Talbot’s invention during Victor La Place excavations at Dūr-Šarrukin (mod. Khorsabad) from 1852-1854 (Fig. 3 and 4; André-Salvini, RlA 13: 419-420). Yet, despite further developments, photography remained relatively expensive during the 19th century and it was only used sporadically.

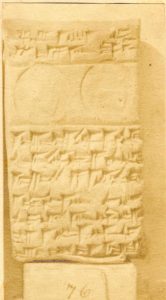

When in 1881 Hormuzd Rassam started to dig at Sippar, he still had to contract a local photographer ad hoc. Contracting a permanent photographer or buying a photographic camera was out of his budget (Reade 1993, 56). On the contrary, employing a photographer in London was less prohibitive. In 1852, Roger Feton, a rising photographer who would found the Royal Photographic Society and document the Crimean War (1853-1856), was commissioned to take photographs at the museum including some 300 clay tablets from the Kuyunjik collection (Fig. 5). Due to the accrued printing costs, these photographs did not replace line-drawings on the publication of cuneiform tablets.

“Pocketification”

In the course of the 20th century, further technical developments – such as the snapshot camera (Fig. 6), the photographic film, or the digital camera – gradually made photography cheaper, portable, and popular. So much so that by now many people have a decent digital camera in their pocket. Meanwhile, an explosion of professional and amateur snappers and photographic subjects followed technological development. The study of the Ancient Near East profited with this iconographic revolution. Early Assyriologists and archaeologists perceived the advantages of photography, and the camera became part of their tool belt. In the field, in the museum, in the reading room or the library, in the lecture hall or in academic events: photography is there.

1000 and 1

The usefulness of photography for the study of the Ancient Near East revealed itself to be manifolded. In the footsteps of Rassam and la Place, excavators and archaeologists continue to use photography to document objects and their work (Fig. 7). In addition, aerial photography (first by airplane, now by drone) proved helpful in mapping sites in complement to plans and line drawings (Fig. 8 and 9).

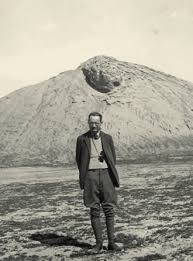

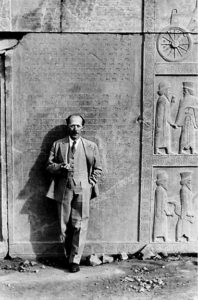

Assyriologists and other enthusiastic visitors recorded their expeditions to Iraq, Iran, and the Levant (Fig. 10 and 11). Museums understood how to benefit from photography as well. There the uses were threefold: to catalogue their collections, to provide context to the exhibits, and to promote their events. Similarly, in academic events and education Assyriology found uses for photography. In talks and in regular courses, slides from objects and sites found their way into serving a didactic and illustrative function. Some Assyriologists found photographic opportunities to be useful for promoting the field in outer and inner communication outlets (Fig. 12).

Another interesting use of photography is the group photograph. It became a standard feature and a cherished tradition of many academic conferences. Such is the case of the group photographs of the Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, the annual meeting of the International Association of Assyriology held since the 1950’s (Fig. 13 and 14).

Objects, tablets, monuments, archaeological sites, expeditions, academic individualities, ceremonies, and celebrations… nothing escaped the eye of the lens. And gladly so! Like Gilgameš’ tablet of lapis lazuli (Epic of Gilgameš I 27), photographic plates and negatives are now being picked up from archives and shedding light on the travails of the “heroes” of Assyriology. By now the amassed wealth of photographic material amassed in 150 years is such that its use as source material for iconography studies, institutional commemorations of the discipline, and creation of virtual museums of Assyriology is warranted (e.g. Achour-Vuurman 2015; The Virtual Museum of Iraq).

“ana ṣât ūmē” – “forever after”

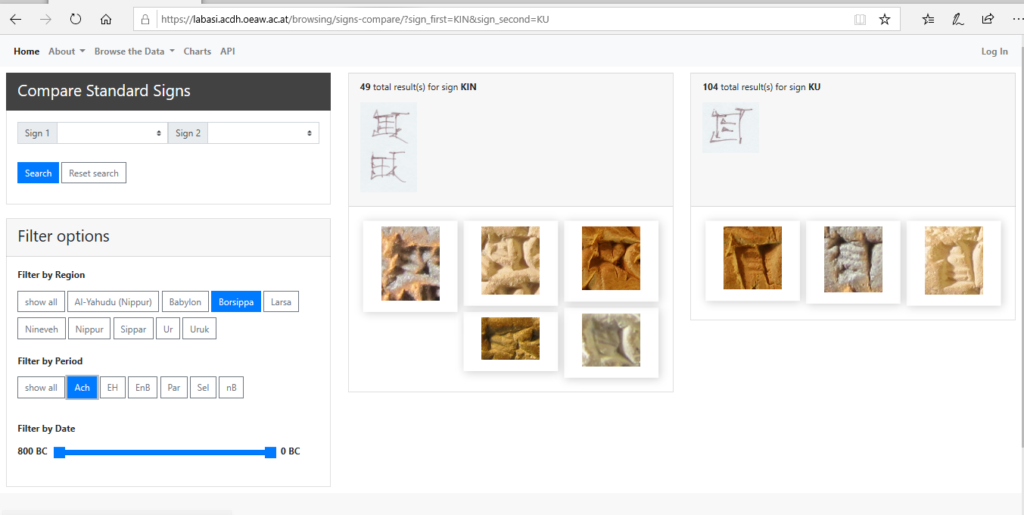

Beyond memory and outreach, photography has an impact on primary research. Quick snapshots of tablets are important assets for personal study in that they virtually expand the limited time researchers have to study original material. More careful photos with controlled lighting are instrumental for the drawing of facsimile copies of a cuneiform tablet. With the help of a macro lens and a remote trigger, it is possible to take close-up photographs of single cuneiform signs which are rarely bigger than a couple of millimetres. Such photos allow the palaeographic study of the form of the sign, the order in which the edges were inscribed, and to detect the presence of small damage and other details invisible to the naked eye (Fig.15). A good example of the palaeographic application of macrophotography is the online sign-list LaBaSi (Fig. 16).

In any case, lighting remains a major factor in dealing with a 3D script. Along with other imaging solutions (e.g. flat scanners; CT-scanner), new techniques are being applied to the study of cuneiform texts which still rely on photography. Examples of this are projects which complement the photographic camera with several sources of light such as RTI and the so-called Leuven Portable Light Dome. These techniques produce two- or three-dimensional digital images of cuneiform tablets (or other artefacts) that later allow remote users to manipulate the source of light as if they were handling the tablet themselves.

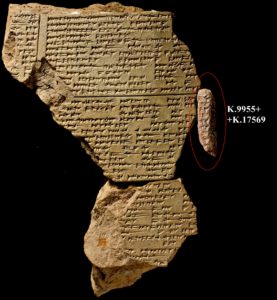

Other projects use photography with a very specific purpose. For instance, the ongoing project Electronic Babylonian Literature promises fascinating results: sweep through thousands of tablets and fragments from the collections of the British Museum and automatically identify joins through an algorithm that analyses images (Fig. 17). The tool for the task is, you guessed it: a photographic camera.

For the last century-and-a-half Photography and Assyriology grew side by side and still learn from each other today. From research to illustration, from outreach to 3D reconstruction of lost artefacts, photography is a jack-of-all-trades for the modern Assyriologist and the camera (be it a specialized one or that small circle on your smartphone) is an indispensable tool on the belt (or pocket) of any researcher and student.

Bibliography

- Achour-Vuurman, C. (2015), Fascinatie voor Persepolis: Europese perceptie van Achaemenidische monumenten in schrift en beeld, van de veertiende tot het begin van de twintigste eeuw, Gronsveld.

- André-Salvini, B. 2019: “Talbot, William Henry Fox”, in M.P. Streck (ed.); E. Ebeling and E. Weidner, Reallexikon der Assyriologie und vorderasiatischen Archaologie 13 (RlA), Berlin and München, 419-420.

- Reade, J. 1993: “Hormuzd Rassam and His Discoveries”, Iraq 55, 39-62.

- Rawlinson et al. 1857: Inscription of Tiglath Pileser I., King of Assyria, B. C. 1150, as translated by Sir Henry Rawlinson, Fox Talbot, Esq., Dr. Hincks, and Dr. Oppert. Royal Asiatic Society and J. W. Parker and Son, London.

Author: Ivo Martins

Published on 5 June 2020