Well into the 19th century traders and travellers’ tales of journeys to the Near East ignited people’s interest. Subsequently museums, newspapers, industrialists or members of the aristocracy funded expeditions to obtain spectacular finds to dazzle their respective audiences with. How did this pursuit for treasures in the 19th century, that entailed a destruction of precious cultural heritage, also instigate the development of a Mesopotamian archaeology?

Whether they were adventurers, merchants or diplomats, the detailed accounts of their trips to the remains of the ancient cities of Mesopotamia stirred people’s imaginations and helped to shape their outlook on the Ancient Near Eastern cultures. These travellers would scribble down their findings, make detailed drawings of landscapes, monuments and inscriptions or even take the first pictures. Armed with the Bible, they vigorously tried to locate cities and monuments, whilst battling sickness, or fending off snakes and robbers along the way. Their reports were published in several languages. Some travellers went even further and were only satisfied by shipping pieces back home.

As early as the 12th century, traveller Benjamin of Tudela described the ruins of the city of Nineveh and wrongly identified the remnants of the ziggurat at Birs Nimrud as the biblical tower of Babel (Benoit 2011, 509; Fagan 2007, 19-21; Matthews 2003, 1).

In the 17th century Italian traveller Pietro della Valle took a few bricks with cuneiform inscriptions from the site of Babylon to Europe. During his subsequent travels to Persia he made many copies of this new, yet unknown script which left many perplexed. From this moment on, many travellers would take his example and make copies of this mysterious script (Benoit 2011, 509-510; Fagan 2007, 29-31; Matthews 2003, 2).

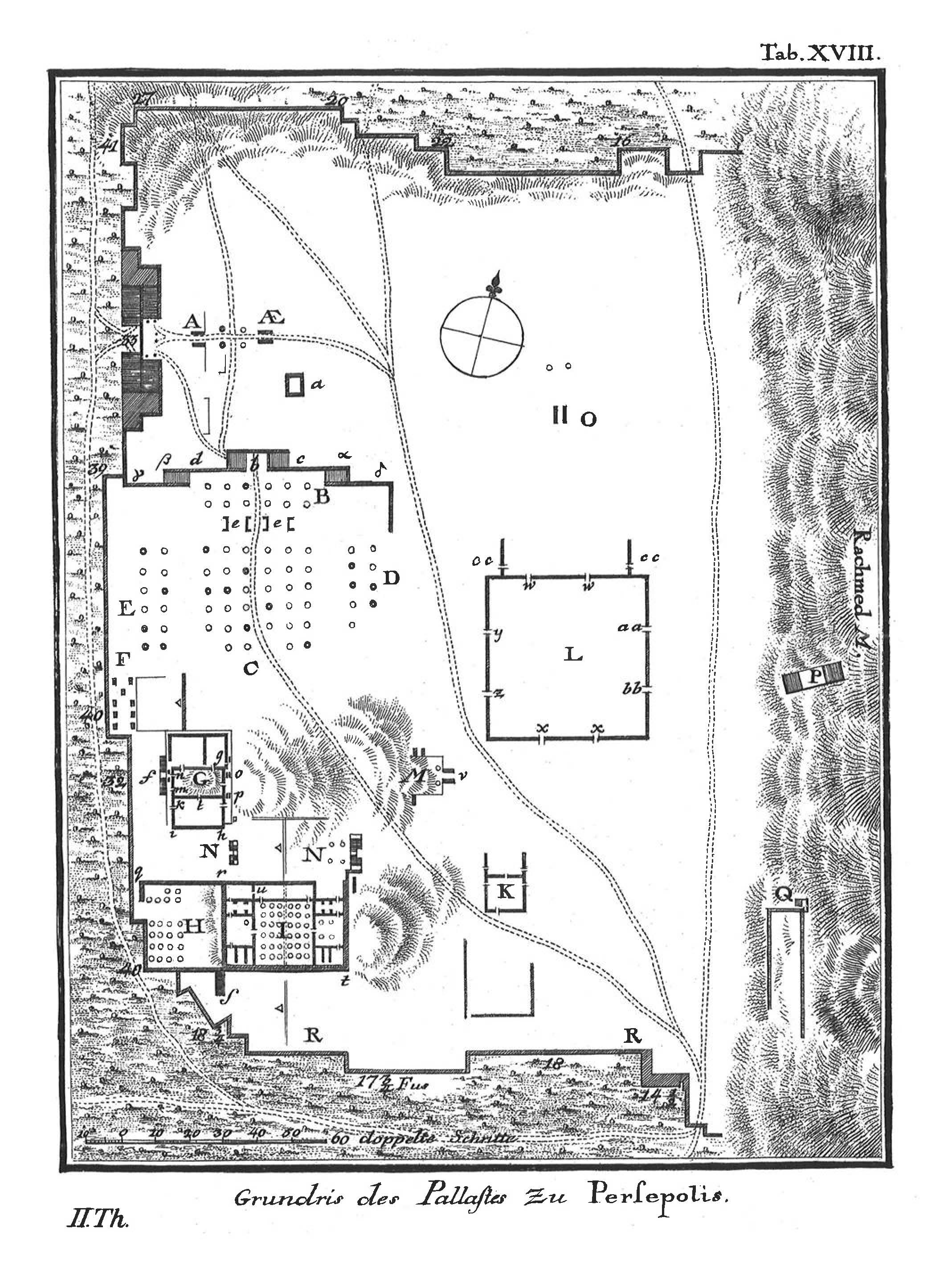

In the 18th century explorer Carsten Niebuhr provided an essential piece of the puzzle for the decipherment of the cuneiform script with his detailed copies of inscriptions at the site of Persepolis. As one of the earliest travellers to explore this site, his account also includes extensive notes and drawings of the landscape and the ancient architecture (Benoit 2011, 511; Fagan 2007, 34-38; Matthews 2003, 2-3).

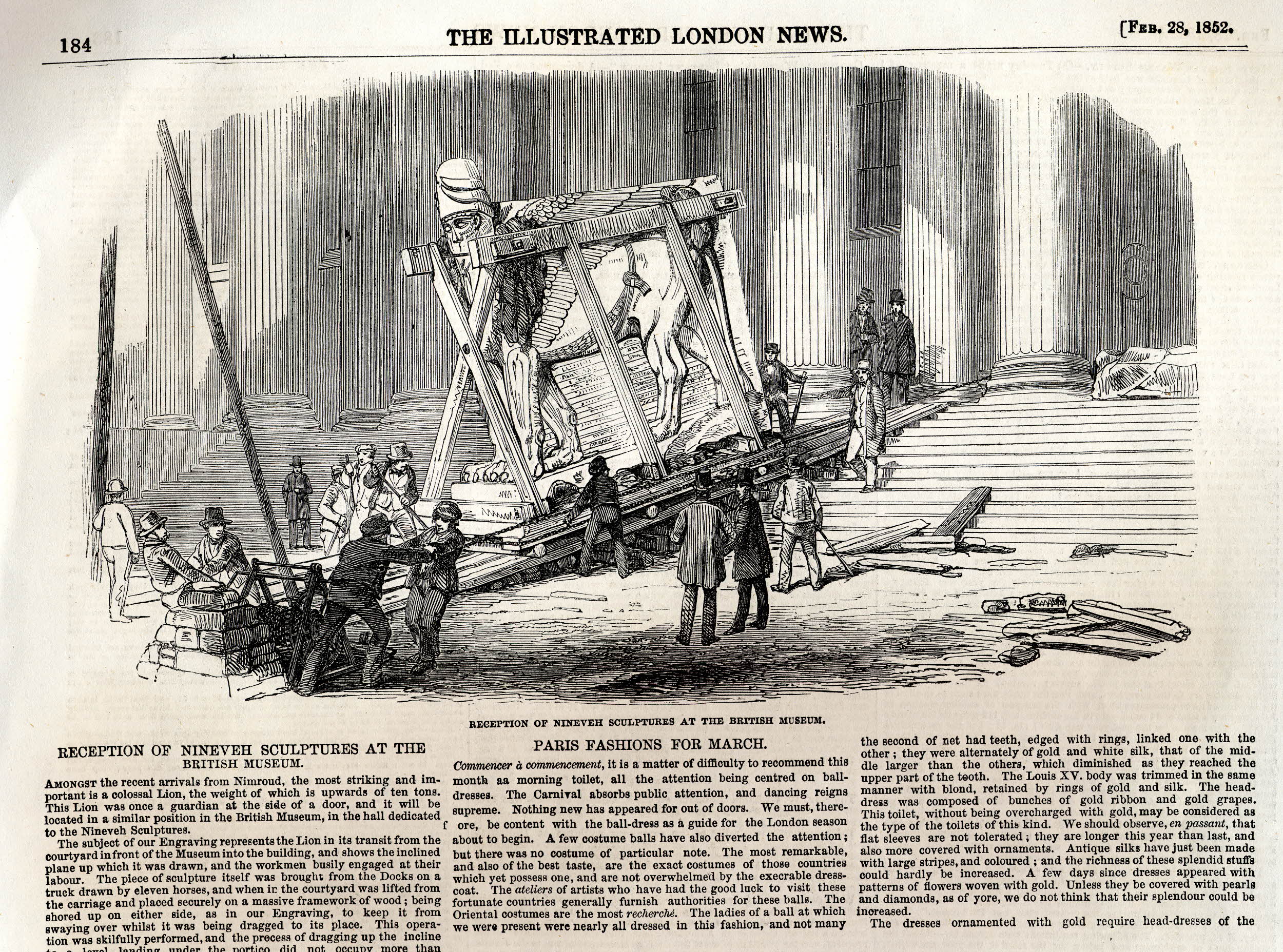

The French diplomat Paul Émile Botta unearthed the palace of Sargon II at Khorsabad. Whilst the English diplomat Austin Henry Layard tunnelled his way through the site of Nineveh. Numerous finds were shipped off to the British museum and the Louvre or to other financiers like members of the aristocracy and rich industrialists. They would use it to embellish their estates or to spruce up their parties (Chevalier 2012, 49-52; Benoit 2011, 515-519; Fagan 2007, 8-9; Matthews 2003, 6-9).

The 19th century excavations came with a cost, as they constituted a large-scale robbery of cultural heritage and a loss of valuable data for present-day and future research. The 19th century excavators hacked their way through multi-period sites, taking no time to properly record the subsequent layers. The stratigraphy of numerous archaeological sites was destroyed. Especially remnants of the most recent periods were ignored and even removed, as the interest of the 19th century excavators lay in what the oldest occupation layers had to reveal and not the youngest. Numerous excavation reports do not contain details about the archaeological find spot of artefacts. Pictures were mostly taken from monumental structures.

At Sippar the 19th century excavations of the Ebabbar temple headed by Hormuzd Rassam unearthed a vast number of cuneiform tablets. But due to a poor registration of the tablets’ archaeological context, at best(!) only the rooms and not the exact find spots of the tablets are known (Matthews 2003, 9-10; Pedersén 1998, 193-197).

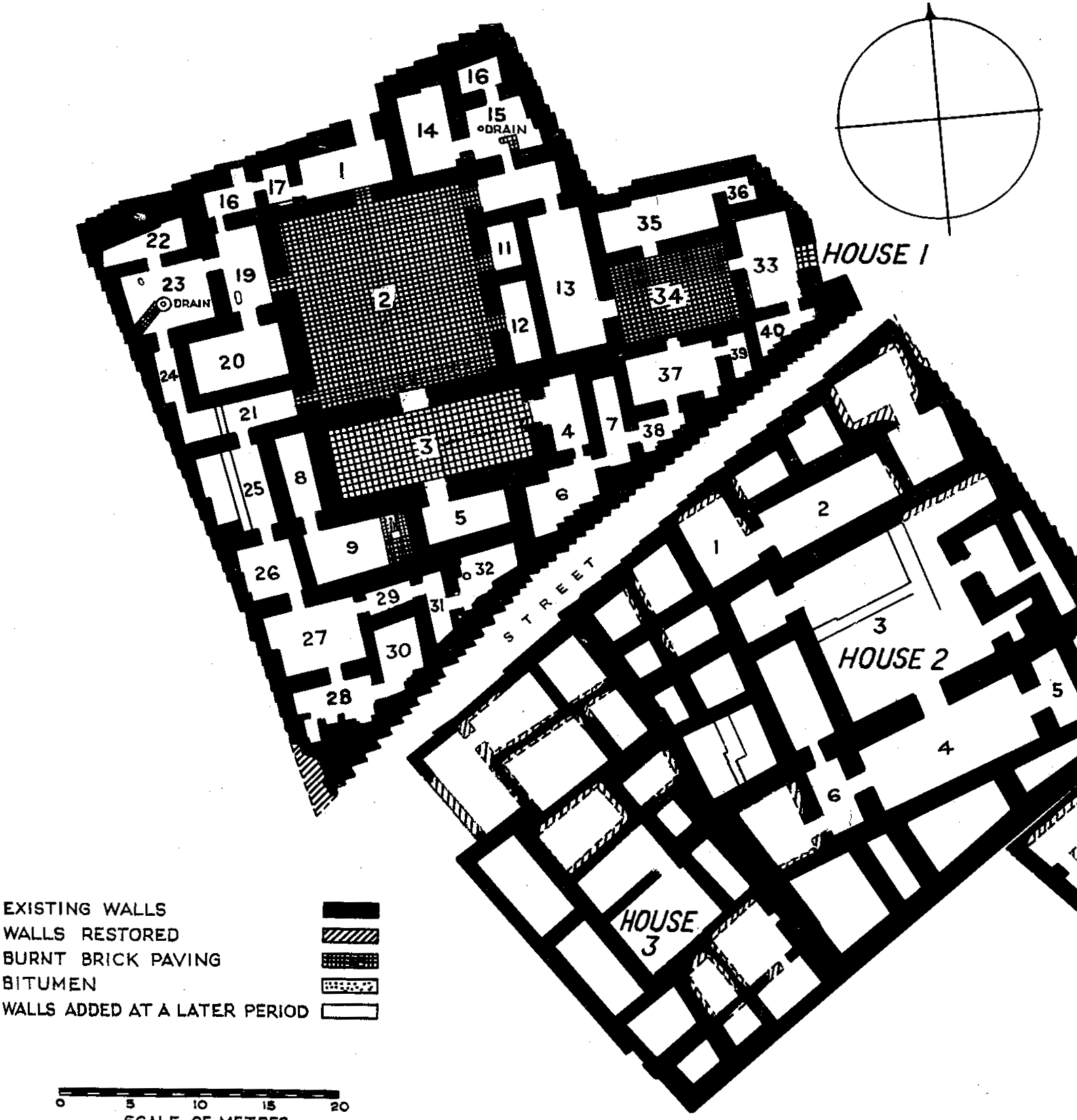

This particular neglect continued well into the 20th century, as can be seen in the excavation reports from Ur. In the 1920s Woolley excavated the residential quarter of the city of Ur dating to the Neo-Babylonian, Persian and Hellenistic periods which is located at the south-eastern part of the town. House 1, with 40 rooms around a central courtyard, dates to the 6th century BCE. Reconstructing the use of space for this house is nearly impossible on the basis of this report alone. Next to the ground plan, it contains only a brief listing of some of the finds per room (Miglus 1999, 177-212, 311-312; Pedersén 1998, 201-204; Castel 1992, 13-17; Woolley and Mallowan 1962, 46-47).

Despite the fact that these early 19th century excavations can be seen as mere treasure hunts, each traveller and excavator contributed in their own way to the development of a Near Eastern Archaeology.

First of all, these early explorers played their part in locating and identifying ancient Mesopotamian cities. Pietro della Valle, for example, was the first to locate the ancient city of Babylon close to Hillah (Benoit 2011, 509).

Secondly, the data provided by the accounts of adventurers, merchants or diplomats is priceless for present-day archaeological research, but also for many other research areas. These accounts contain descriptions, drawings or pictures of the architecture and the landscape that are now lost due to modern urbanization, looting and war. These travel accounts also elaborate on the daily life, local customs, religious life and the political situation in the Near East. Carsten Niebuhr, for example, describes and illustrates the musical instruments, the local dress and the water management systems that he encountered during his travels.

The most significant change however came after 1870 when more refined scientific methods and techniques were being introduced.

Archaeologist Dorothy Garrod, with her systematic and thorough research of the Near Eastern prehistory, analysed with precision skeletons and flints. She also preferred the use of radiocarbon dating over relative dating methods (Renfrew and Bahn 2016, 33-35, 38-39; Davies 1999, 6-10)

Archaeologist Robert Koldewey initialized the detection, recording and excavation of mudbrick walls (Chevalier 2012, 60-61; Fagan 2007, 9-10; Matthews 2003, 10-12).

More importantly, Garrod and Koldewey’s work methods and techniques were passed on to their assistants and students who represented the future of Ancient Near Eastern Archaeology. Walter Andrae took the knowledge he had gained from Koldewey and performed the first stratigraphic sounding at the temple of Ištar at the ancient site of Assur (Chevalier 2012, 60-61; Fagan 2007, 9-10; Matthews 2003, 12). From then on, we can truly start to speak of an Ancient Near Eastern Archaeology.

Bibliography

- Benoit, A. 2011: Les Civilisations du Proche-Orient Ancien (Petits Manuels de L’École du Louvre), Paris.

- Castel, C. 1992: Habitat urbain Néo-Assyrien et Néo-Babylonien. De l’espace bâti (…) à l’ espace vécu (Bibliothèque archéologique et historique de l’Institut français d’archéologie du Proche-Orient 143), Paris.

- Chevalier, N. 2012: “Early Excavations (pre-1914)”, in D.T. Potts (ed.), A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. Volume II, Oxford, 48-69.

- Davies, W. 1999: “Dorothy Annie Elizabeth Garrod: A Short Biography,” in W. Davies and R. Charles (eds.), Dorothy Garrod and the Progress of the Palaeolithic. Studies in the Prehistoric Archaeology of the Near East and Europe, Oxford, 1-14.

- Fagan, B.M. 2007: Return to Babylon. Travelers, Archaeologists and Monuments in Mesopotamia (Revised Edition), Colorado.

- Matthews, R. 2003: The Archaeology of Mesopotamia: Theories and Approaches (Approaching the Ancient World), London.

- Miglus, P.A. 1999: Städtische Wohnarchitektur in Babylonien und Assyrien (Baghdader Forschungen 22), Mainz.

- Niebuhr, C. 2018: Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegenden Ländern (reprint) (Foliobände der Anderen Bibliothek 20), Berlin.

- Pedersén, O. 1998: Archives and Libraries in the Ancient Near East 1500-300 B.C., Bethesda.

- Renfrew, C. and P. Bahn 2016: Archaeology: Theories, Methods and Practice (Seventh Edition), London.

- Woolley, L. and M. Mallowan 1962.: The Neo-Babylonian and Persian Periods (Ur Excavations 9), London.

Author: Evelien Vanderstraeten

Published on 18 June 2019