By Ivo Dos Santos Martins

When the last rays of sun were rolling out, as the days grew cold, the trees unfolded and the lectures and borrels began in Leiden, I found myself lost in London. I have flown across the Channel to enjoy a two-month-long self-imposed academic exile in this Babylon-on-Thames in the wake of a “mad” king.

The Fighting Téméraire last port-of-call

I was based on the borough of Southwark for the duration, not very far from the 00o00’ 00” meridian. This part of London has a suburban feeling to it. Being a suburban boy, I quite enjoyed the neighbourhood. It is so peaceful and quiet that foxes cross the streets during the day just as freely as they do at night [Fig. 1].

I was able to visit a few of the many public parks London has to offer: Greenwich [Fig. 2], St. James, Southwark, Hyde Park etc. These are all excellent green oases in the heart of this Babylon-on-Thames. And yet, I confess that I liked the smaller and unknown Russia Dock Woodland park and its Stave Hill [Fig. 3] better, as it often served as scenery for my sleepless nights.

Moreover, the neighbourhood is steeped in history. During the last two centuries, this area was a lively commercial port welcoming inbound ships from Canada, Russia etc. It was also here that the HMS Téméraire, a ship-of-the-line which fought at Trafalgar, found its last port-of-call and was dismantled in 1838. Nowadays, the docks are either drained and turned into parks or have simply become leisure wharves; while the Fighting Téméraire’s last voyage lives on eternalised by the lively strokes of Turner [Fig. 4].

There and back again: the routine

Each day I cross the clayish waters of the Thames to the heart of London. I spend my days around Bloomsbury and Fitzrovia, but mostly around Russel Square. After roughly one hour of commuting, I reach the square around eight a.m. Both the SOAS Library and the British Museum are still closed, so I bide my time reading at the Square or in a nearby café. At nine in the morning, I enter SOAS Library to continue my work in a more quiet place.

Alas, by 10:15 a.m. I must be on the move making my way to the British Museum [Fig. 5]. I still need to go through security and on no circumstance will I be late for the rare chance to read a twenty five hundred year old piece of history. As is to be expected, security is a big concern at the museum. All visitors and their bags are thoroughly checked every time they enter.

Within the museum, the same zealous attention applies. It has been somewhat tricky to access the Middle East Reading Room at the British Museum, as the shop, which serves as an antechamber to this Reading Room, is officially closed. Often, the security personnel deniesstudents access or locks the doors while the students are still inside the room.

Thankfully, the Reading Room staff has been equally zealous in solving the situation. It will surely be solved from November onwards, once the new exhibition opens its doors.

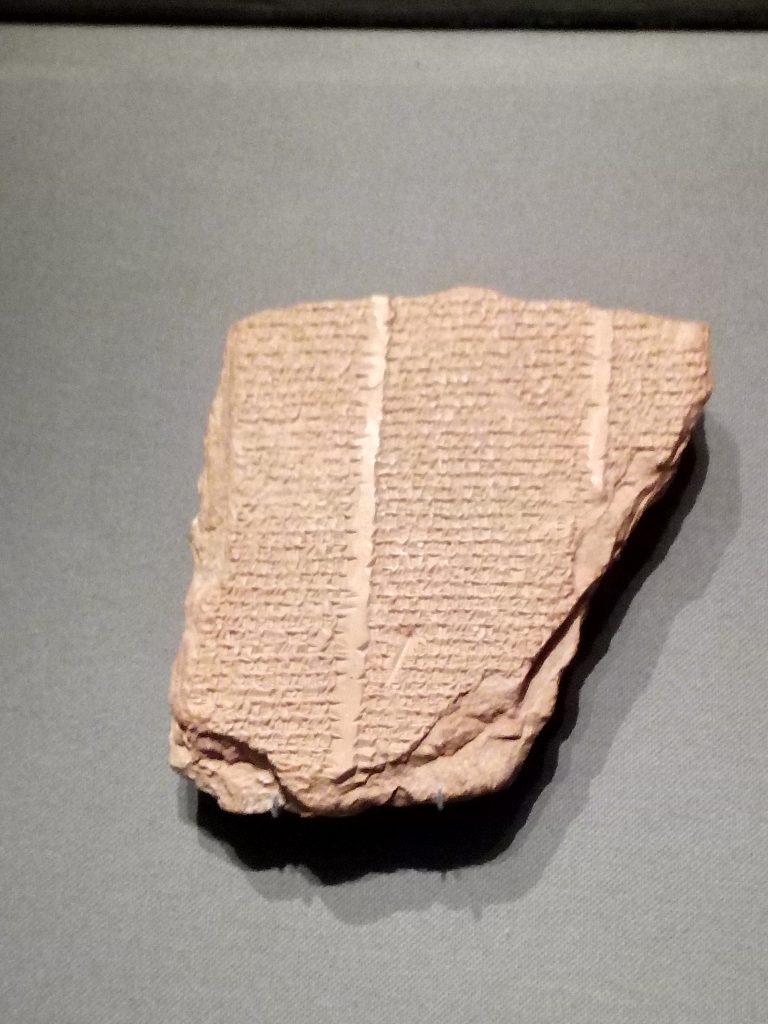

Once I gain access to the Reading Room, I take my place on one of the long old wooden tables. In front of me, there is always a small black mat, a lamp, and a large upholstered wooden tray labelled with my name. On it, there are fifteen clay tablets or fragments. Most objects have their own cardboard box, in which they rest upon a cotton bed. Some bigger objects such as joined literary tablets or cylinders lack such a box. Curiously, students are only required to wear gloves when handling metal objects and pottery sherds. When handling tablets made of clay, such precaution is not observed.

What lays ahead are five and a half hours to study, copy and read millenary royal inscriptions, literary fragments of wisdom and historical writings that show but a glimpse of political and intellectual world of Babylon during the first millennium BCE.

As if that was not enough, the Reading Room merits a visit by itself. Under its high ceiling the study of the Middle East is disposed on two floors. The first floor harbours a library, used by the department staff, and wide windows designed to flood the room with light; the ground floor, divided into twelve bays with eleven tall cabinets each, houses but a small portion of the cuneiform collections owned by the museum.

At 4 p.m. the Reading Room closes for visitors. Packing my things, I cross Montague Place and Russell Square in the opposite direction and return to the library of School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). The SOAS Library with its four open levels full of books is impressive. And it is also useful, once you crack the peculiar reference system. Here, cramped into a small workspace, I spend the remainder of my time. Normally, I check the readings done during the day, read on my research topic and try to write. When SOAS Library closes, I board the 188 and head back to suburbia. Tomorrow will be another day.

Some other time perhaps…

At its inception, this research trip to London had two main objectives. The first one has a somewhat broad scope, namely to gain some experience in reading and collating Neo- and Late Babylonian cuneiform tablets. The second aim, more zeroed in on my current PhD research, was to access, collate and copy an important literary text from that same period.

This tablet, which has been published twice before, is commonly known as the Verse Account [Fig. 6]. Usually, this artefact is displayed at the British Museum as a highlight concerning the last Babylonian monarch, Nabonidus. Due to its popularity and the fact that it is on display, it is difficult to gain access to this source. However, for the time being, it is even harder to gain access to the source than usual. As it turns out, the artefact is part of an exhibition on political dissent through the ages, guest curated by Ian Hislop. Unfortunately, this central objective has to be postponed. Yet, more than enough tablets are accessible to me, so I will be able to fulfil my secondary aim.

A museum of the world, for the world

By now, the British Museum is an old and cherished institution both in and outside the United Kingdom. It is both a cultural centre hosting various events and also modern art; and a house of tradition where the wall clocks are still winded by hand every now and then…

Nowhere else is this respect for tradition more manifest than in the so-called Enlightenment Gallery. This gallery aims to reproduce the original configuration of the museum. Two hundred and sixty tall cabinets exhibit books and artefacts, several display cases are disposed through the hall. Classical statues intermingled with modern ones, representing the first curators and Sir Hans Sloan, the “spiritual founder” of the museum, lay around the room. And, testifying that the early inclinations of the institute were just as vast and international as the modern ones, a replica of the Rosetta Stone is also on display here, upon a display stand similar to the one which held the real artefact in 1801.

Despite its name, The British Museum has indeed become “grande maison des étrangers” as an anonymous prophet announced in 1845 [1]. But, contrary to his calamitous view, this is a good thing. From staff to visitors, the world comes here to tend to and to see the treasures of the world. Moreover, the museum is an important asset for research fields with an international standing such as Assyriology. This worldwide scope has been the main argument presented by the British Museum when ownership of possessions such as the Elgin Marbles are contested. These worldwide famous archaeological remains, named after the British official who secured their acquisition and transport to the museum, were once part of the Parthenon in Athens. There is a lively debate on whether these marbles should remain at the British Museum or if they should be returned to Athens’ Acropolis Museum.

Babylon-on-Thames AKA London

On Sundays, I take a leave from work. Its time bury my thoughts on something else and explore the city. All and all, I expected a much darker and more oppressive metropolis. Gratefully, the heavy smog is now only a thing of memory enclosed on the pages of Dickens, and hopeful billboards announce zero emissions in the city centre in a near future.

And, as the cherry on top, the last and resilient Summer days mostly keep rain and fog away. It is nice to stroll along the banks of the Thames [Fig. 7], to walk in the public parks and to chase squirrels and foxes around. It is equally good to enjoy the many free of charge museums like the Tate Modern (which besides contemporary art offers a great view of the city [Fig. 8]) or the Museum of Natural History in Kensington with its majestic hanging blue whale skeleton [Fig. 9].

More interesting still is the city itself and its people. This is truly a Babylon-on-Thames: diverse and multicultural. Several communities live here together, everyone goes about their daily strife shoulder to shoulder. And yet, this Babylon is not just a majestic, beautiful and lively city, there’s a darker side as well. Just take a short bus ride and pay attention. You will see several young and able-bodied men sleeping on the streets and under the bridges. For them, this city is all but beautiful or kind.

In any case, because I am only a tourist here, I can still find some charm to the city and its views. It is amazing to see how the old and the new play with each other [Fig. 10]. I especially like the way the history encroaches itself on the modern city [Fig. 11 and 12], or rather the solutions the modern city has found to preserve and embrace the old cities of London [Fig. 13]. The whole city feels like an open-air museum.

With all said, seen and done, it is about time to wander on to other shores and say: Dear, damn’d distracting town, farewell! [2][Fig. 14].

[1] “Situations in the Museum, as they became vacant by death – no one ever retires – are given to German and Italian boys; so that in time our great national institution will be one grande maison des étrangers” ‘Correspondent of the Edinburgh Review’ 1845, Madden collection, fol. 85 in Millard, Edward (1974) That Noble Cabinet: A History of the British Museum: 172.

[2] Alexander Pope, “A Farewell to London”.

* This study trip was sponsored by Leiden University Fund/Dr. C.L. van Steeden Fonds and the ERC Project Persia and Babylonia.