By Evelien Vanderstraeten

Game of Thrones… I know… Don’t worry! It will only get worse.

References, one-liners and memes will appear in abundance on social media, as we are so close to the air date of the eighth and final season of this fantasy TV show. Finally the battle for the Iron Throne will come to an end and the identity of the one true ruler will be revealed. Or so we hope!

But how can we, busy scholars, research assistants and students (aka secret fantasy lovers), dying with anticipation and greedy to know more, make do in the meantime?

Straight answer… by finding as much historical precedents as possible and maybe even a topic or two for upcoming conference talks! Ah… solace and answers can be found in cuneiform texts, artefacts and in the exquisite British Museum exhibition “I am Ashurbanipal”.

A King’s fight

To become king of the Neo-Assyrian empire members of the royal court plotted, fought and even resorted to murdering their kin during ferocious revolts. As king of Assyria, Sennacherib (705-681 BCE) was assassinated in an uprising led by a couple of his sons. They were enraged with the appointment of their younger brother Esarhaddon as crown prince. Esarhaddon (681-669 BCE) however crushed their revolt, thus claiming his rightful place as heir to the throne.

Due to his own first-hand experience of the destructive nature of sibling rivalry, he contrived a way to avoid the same thing happening to his sons. He bequeathed them each a seat of kingship. In 672 BCE he appointed Ashurbanipal as his successor and made him crown prince of Assyria, while making Šamaš-šumu-ukīn the crown prince of Babylon.

The king is dead, long live … two kings: šar mātāti and šar Bābili

A glimpse of the new political power relation between Ashurbanipal and Šamaš-šumu-ukīn, after the death of their father, can be seen through their titles in legal documents. As research assistants for the open access database Prosobab we plough through several cuneiform texts a day, gathering and inserting social data of the men and women living in Babylonia around 690-330 BCE. These promissory notes, receipts, sale contracts, testaments, etc. are dated to the regnal year of kings. As such, the name and the title of these kings enter the database.

Certain tablets from the Ea-Ilūtu-bānī, Ilī-bāni and Nanāhu; Šamšēa; Sîn-nāṣir and Šumāya archives date to the reign of Šamaš-šumu-ukīn (667-648 BCE). As king of Babylonia he carried the title šar Bābili. A few texts in our database date to Ashurbanipal’s reign (669-627 BCE). In contrast to his brother, he held the title of šar mātāti or king of the lands as he ruled over the entire Assyrian empire reaching from Cyprus in the west to western Iran in the east.

A spy master, a vassal king and a rebellion

To stay king of the Neo-Assyrian empire and to suppress any other claim to the throne Ashurbanipal had an arsenal of political tools at his disposal. One of his most important victims was his older brother Šamaš-šumu-ukīn. As a true spymaster with agents across the empire, he kept a close eye on everything his brother did. Babylonia belonged to the Neo-Assyrian empire and on numerous occasions Ashurbanipal clipped his brother’s wings to ensure that he would not rule separately. For instance he made sure that Babylonia did not have a military army of its own. Šamaš-šumu-ukīn was reduced to being nothing more than a puppet king. This instigated Šamaš-šumu-ukīn’s rebellion in 652 BCE and meant the end of their father’s carefully contrived plan.

Game for the throne

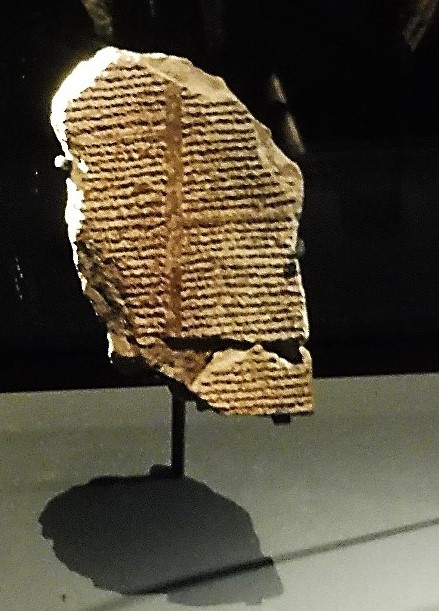

The rivalry between the two brothers was nicely brought to life by one particular museum display cabinet at the “I am Ashurbanipal” exhibition. It contained among other an unpublished letter from Šamaš-šumu-ukīn to his brother Ashurbanipal and a fragment of a board game.

In this letter Šamaš-šumu-ukīn provokes his brother by reminding him on how he used to beat Ashurbanipal during one of their favorite pastimes as children: board games. He tells him how he will once again outplay Ashurbanipal and in doing so conquer his throne.

Alas, Šamaš-šumu-ukīn did not win the throne of the Neo-Assyrian empire. His rebellion was crushed by Ashurbanipal in 648 BCE after much effort and a protracted siege of the city of Babylon. Ashurbanipal remained the true ruler of the Neo-Assyrian empire and put Kandalānu (647-627 BCE) as a vassal king on the throne of Babylonia.