By Uzume Wijnsma

Anyone who is familiar with the NINO (Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten) knows how precious its collection of antiquities is. Ca. 3000 cuneiform tablets are stored in the institute – the largest collection of its kind in the Netherlands. One can also find a variety of seals, statuettes, and terracotta heads (et cetera) among its possessions. It is always exciting to open one of the drawers in the NINO vault to see what you can find among its tiny treasures. A few months ago, I did just that – and I found a few pieces that I immediately fell in love with.

The pieces I fell in love with are twenty-two small lumps of clay, nowadays known as LB 893 – 914. They are roughly triangular in shape. And none of them look particularly interesting at first sight. If one didn’t know any better, one could think that they were nothing more than tiny lumps of ancient mud. Or, as a friend of mine thought when I sent them a picture: a series of oddly shaped cookies. But I promise you they are more than that.

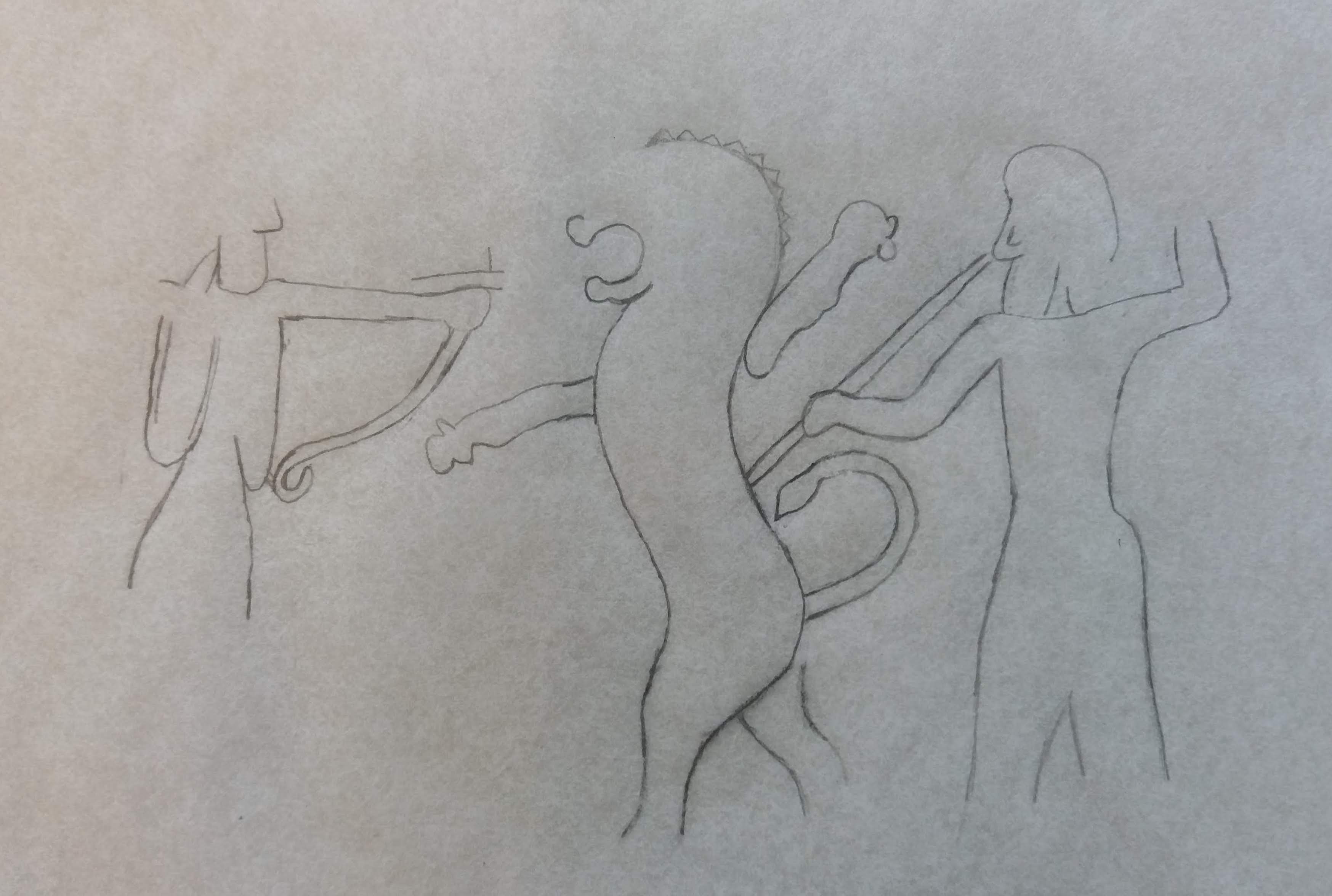

The muddy triangles-cum-cookies are, in fact, bullae – a fancy word for inscribed or sealed tokens. If one holds the bullae under the lamplight, one can see traces of seals that were impressed into the clay many hundreds of years ago. The impressions in the NINO are particularly beautiful (if you ask me). One seal impression, for example, shows a lion whose jaws bite into the back of a tender stag. Another shows two men who are hunting a running boar. A third shows a man spearing another human being. Every image is vibrant and lively in its own specific way. And the style of the images indicates that they are Achaemenid in date (ca. 550 – 330 BC) – which probably explains why I, Achaemenid nerd, am so fond of them.

I was fortunate enough to be able to study the seal impressions with Mark Garrison – expert of Achaemenid glyptic par excellence – ca. a week ago. We spent a rainy Saturday in an otherwise deserted NINO library, staring at the tiny images and trying to draw them as accurately as possible. A tail here, a nose there. A spear that drills into the back of a lion. A crown on that guy’s head. Hours and hours of looking at these wonderful pieces: drawing a line, erasing it, drawing it again, erasing it, trying it a third time – until you get it exactly right. It was difficult but lovely work. Copying an image by hand gives you an understanding of its details that a photograph just cannot. You begin to see every nook and cranny of a scene. Every tiny feature. Something that is indispensable, of course, for a correct interpretation of the image.

So where do these bullae come from? Well, we actually don’t really know. None of the pieces has a recorded find spot. That also applies to bullae in other collections: pieces of similar shape and with exactly the same seal impressions were found in collections in Germany, France and the USA. The NINO, with twenty-two different pieces, holds the largest single collection. But the original find must have consisted of more than forty tokens. What the bullae were used for remains equally obscure. It is possible that they used to seal papyrus rolls or storage devices. Or perhaps they served some independent administrative purpose of their own. As we lack an archaeological (or archival) context, we are left to guess. Frustrating as that is.

Whatever the original function of the bullae was, however, their seal impressions remain. And they are interesting in their own right. The images show us how people who lived ca. 2500 years ago imagined their own surroundings and society. They indicate what was important to them (ideologically or otherwise), and how they thought it should be represented. The seals, in other words, form tiny windows onto the world of the Achaemenid Empire. And they show us a world of dangerous animals, of royal hunting and of warfare.

To have that information preserved is treasure enough, I’d say. And to slightly paraphrase a cliché: a seal impression is worth a thousand words. Is it not? 😉

Bibliographical note:

The bullae from the NINO (and similar bullae from other collections) were published in 2004 by Wouter Henkelman, Charles Jones and Matthew Stolper. You can visit this link for their wonderful article: http://www.achemenet.com/pdf/arta/2004.001.pdf (with plenty of photographs; but, unfortunately, without modern drawings).

Do note that other specimens of the same corpus have popped up since then. The whereabouts of LB 914, for example, the twenty-second piece in the NINO, were unknown in 2004. But it is here now!